17 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

To Stop Fentanyl Deaths in Philadelphia, Knocking on Doors and Handing Out Overdose Kits

On a narrow street lined with row houses and an auto body shop in the Kensington neighborhood of North Philadelphia, Marsella Elie climbs a home’s front steps and knocks hard on the door.

A middle-aged man appears with a wary look on his face.

“Hello, sir, how are you doing today?” asked Elie, wearing a royal-blue jacket embroidered with the city government’s Liberty Bell logo. “My name is Marsella. I’m working with the city. You heard about the overdoses that are going around in the neighborhood, right?”

The man gives a cautious nod.

Elie gestures to the pamphlets she’s holding about drug overdoses and addiction treatment programs. She holds up a box of Narcan, a brand of naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose.

“What we’re trying to do is get this in everybody’s household. Have you ever heard of this before?” Elie asked before handing the man a tote bag filled with more pamphlets, fentanyl test strips, and the box of Narcan.

Elie and other part-time city workers and volunteers are part of a large-scale, citywide door-to-door campaign in Philadelphia that aims to equip homes with naloxone and other drug overdose prevention supplies.

City officials hope that this proactive approach will normalize naloxone as an everyday item in the medicine cabinet, and prevent people from dying of overdoses, especially Black residents.

In Philadelphia in 2022, a record 1,413 people died from drug overdoses, according to city data. Among Black residents, deaths were up 20% from the year before, with many happening in private homes.

“The best thing we can do to make these things more accessible is to just give them to people,” said Keli McLoyd, deputy director of the city’s Opioid Response Unit, speaking about the tote bag with naloxone and other supplies. “We’re not asking you if you’re using drugs. The goal here is really to build sort of a collective responsibility. As Black and brown folks, as we saw during the covid epidemic, nobody’s coming to save us. For us, this is a tool that we can use to save ourselves.”

The canvassing initiative aims to take prevention supplies directly to people who might not otherwise seek it out themselves, and to spread awareness about overdoses beyond Kensington, the epicenter of the city’s addiction epidemic. Canvassers plan to knock on more than 100,000 doors in Philadelphia’s “hot spots” — ZIP codes with escalating rates of opioid overdoses, many in minority communities.

Widening racial disparities in overdose deaths are among the long-term consequences of the war on drugs, McLoyd said. Policies from that national anti-drug campaign led to decades of aggressive police tactics, racial profiling, and lengthy prison sentences, disproportionately affecting people of color and their communities.

Research shows that Black Americans still account for a disproportionate number of drug arrests and child protective services.

“Because of that, it’s very clear why Black or brown people might be hesitant to raise their hand and say, ‘I’m a person who uses drugs, I need those resources,’” McLoyd said.

Other communities have distributed naloxone and other supplies, albeit on a smaller scale than Philadelphia.

What Philadelphia is doing could become a model for other densely populated places, said Daliah Heller, vice president of drug use initiatives at Vital Strategies, a public health organization working with local governments in seven states to address the opioid epidemic.

“There’s something intensely personal about a human engagement,” Heller said. “And somebody knocking at your door to talk about drug use and overdose risk and that there’s something that can be done, I think is really powerful.”

Over the years, naloxone has become more accessible than ever before, Heller pointed out. It can now be ordered online and through the mail, it’s available in specialized vending machines, and some drugstores now sell Narcan nasal spray over the counter.

But tens of thousands of Americans are still dying from opioid overdoses every year. That means prevention efforts and messaging about the crisis are still not reaching some people, Heller said. And to her, reaching people means meeting them where they are. “That means physically, that means in terms of what they know about something, what their perception is of something, and their beliefs,” she said. “We need to think like that when we think about naloxone distribution.”

The Philadelphia canvassing project is funded in part by the city’s share of settlement payouts from national lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors. The city is set to receive about $200 million over roughly 18 years from settlements with AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson, and Johnson & Johnson.

The initiative is staffed by many of the same people who initially started canvassing as part of the 2020 census count.

Not everyone answers the door for the canvassers. Some aren’t home when they come around. In those cases, workers hang a flyer on the door handle that offers information about overdose risks and contacts for further resources. The teams of canvassers, often with language interpreters, later make a second sweep through a neighborhood to reach people they missed the first time.

On a recent Thursday, Philadelphia canvassers were knocking on doors in the Franklinville and Hunting Park neighborhoods. In this ZIP code, about 85 people died of drug overdoses in 2022, according to city data. That’s fewer than the 193 people who died of overdoses in Kensington in 2022, but much higher than the few deaths seen in the city’s most affluent neighborhoods.

The canvassers approached a resident, Katherine Camacho, on the sidewalk, as she came out of her garage. Camacho told the teams she was aware of the overdose problem in her community and then eagerly accepted a box of Narcan.

“I will carry this with me, because, like I said, sometimes you’re in the street driving somewhere and you could save a life,” Camacho told them. “And if you don’t have these things, it’s harder to do so, right?”

Camacho said she’s seen how the opioid crisis has caused suffering in her neighborhood and across the city. As for Philadelphia’s canvassing effort, she said she believes that “God is putting these people to help.”

As she headed into her house carrying the box of Narcan, Camacho said she wanted to do her part to help, too.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

17 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

Native Americans Have Shorter Life Spans. Better Health Care Isn’t the Only Answer.

HISLE, S.D. — Katherine Goodlow is only 20, but she has experienced enough to know that people around her are dying too young.

Goodlow, a member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, said she’s lost six friends and acquaintances to suicide, two to car crashes, and one to appendicitis. Four of her relatives died in their 30s or 40s, from causes such as liver failure and covid-19, she said. And she recently lost a 1-year-old nephew.

“Most Native American kids and young people lose their friends at a young age,” said Goodlow, who is considering becoming a mental health therapist to help her community. “So, I’d say we’re basically used to it, but it hurts worse every time we lose someone.”

Native Americans tend to die much earlier than white Americans. Their median age at death was 14 years younger, according to an analysis of 2018-21 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The disparity is even greater in Goodlow’s home state. Indigenous South Dakotans who died between 2017 and 2021 had a median age of 58 — 22 years younger than white South Dakotans, according to state data.

Donald Warne, a physician who is co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health and a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, can rattle off the most common medical conditions and accidents killing Native Americans.

But what’s ultimately behind this low life expectancy, agree Warne and many other experts on Indigenous health, are social and economic forces. They argue that in addition to bolstering medical care and fully funding the Indian Health Service — which provides health care to Native Americans — there needs to be a greater investment in case management, parenting classes, and home visits.

“It’s almost blasphemy for a physician to say,” but “the answer to addressing these things is not hiring more doctors and nurses,” Warne said. “The answer is having more community-based preventions.”

The Indian Health Service funds several kinds of these programs, including community health worker initiatives, and efforts to increase access to fresh produce and traditional foods.

Private insurers and state Medicaid programs, including South Dakota’s, are increasingly covering such services. But insurers don’t pay for all the services and aren’t reaching everyone who qualifies, according to Warne and the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Warne pointed to Family Spirit, a program developed by the Johns Hopkins center to improve health outcomes for Indigenous mothers and children.

Chelsea Randall, the director of maternal and child health at the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, said community health workers educate Native pregnant women and connect them with resources during home visits.

“We can be with them throughout their pregnancy and be supportive and be the advocate for them,” said Randall, whose organization runs Family Spirit programs across seven reservations in the Dakotas, and in Rapid City, South Dakota.

The community health workers help families until children turn 3, teaching parenting skills, family planning, drug abuse prevention, and stress management. They can also integrate the tribe’s culture by, for example, using their language or birthing traditions.

The health board funds Family Spirit through a grant from the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, Randall said. Community health workers, she said, use some of that money to provide child car seats and to teach parents how to properly install them to counter high rates of fatal crashes.

Other causes of early Native American deaths include homicide, drug overdoses, and chronic diseases, such as diabetes, Warne said. Native Americans also suffer a disproportionate number of infant and maternal deaths.

The crisis is evident in the obituaries from the Sioux Funeral Home, which mostly serves Lakota people from the Pine Ridge Reservation and surrounding area. The funeral home’s Facebook page posts obituaries for older adults, but also for many infants, toddlers, teenagers, young adults, and middle-aged residents.

Misty Merrival, who works at the funeral home, blames poor living conditions. Some community members struggle to find healthy food or afford heat in the winter, she said. They may live in homes with broken windows or that are crowded with extended family members. Some neighborhoods are strewn with trash, including intravenous needles and broken bottles.

Seeing all these premature deaths has inspired Merrival to keep herself and her teenage daughter healthy by abstaining from drugs and driving safely. They also talk every day about how they’re feeling, as a suicide-prevention strategy.

“We’ve made a promise to each other that we wouldn’t leave each other like that,” Merrival said.

Many Native Americans live in small towns or on poor, rural reservations. But rurality alone doesn’t explain the gap in life expectancy. For example, white people in rural Montana live 17 years longer, on average, than Native Americans in the state, according to state data reported by Lee Enterprises newspapers.

Many Indigenous people also face racism or personal trauma from child or sexual abuse and exposure to drugs or violence, Warne said. Some also deal with generational trauma from government programs and policies that broke up families and tried to suppress Native American culture.

Even when programs are available, they’re not always accessible.

Families without strong internet connections can’t easily make video appointments. Some lack cars or gas money to travel to clinics, and public transportation options are limited.

Randall, the health board official, is pregnant and facing her own transportation struggles.

It’s a three-hour round trip between her home in the town of Pine Ridge and her prenatal appointments in Rapid City. Randall has had to cancel several appointments when family members couldn’t lend their cars.

Goodlow, the 20-year-old who has lost several loved ones, lives with seven other people in her mother’s two-bedroom house along a gravel road. Their tiny community on the Pine Ridge Reservation has homes and ranches but no stores.

Goodlow attended several suicide-prevention presentations in high school. But the programs haven’t stopped the deaths. One friend recently killed herself after enduring the losses of her son, mother, best friend, and a niece and nephew.

A month later, another friend died from a burst appendix at age 17, Goodlow said. The next day, Goodlow woke up to find one of her grandmother’s parakeets had died. That afternoon, she watched one of her dogs die after having seizures.

“I thought it was like some sign,” Goodlow said. “I started crying and then I started thinking, ‘Why is this happening to me?’”

Warne said the overall conditions on some reservations can create despair. But those same reservations, including Pine Ridge, also contain flourishing art scenes and language and cultural revitalization programs. And not all Native American communities are poor.

Warne said federal, state, and tribal governments need to work together to improve life expectancy. He encourages tribes to negotiate contracts allowing them to manage their own health care facilities with federal dollars because that can open funding streams not available to the Indian Health Service.

Katrina Fuller is the health director at Siċaŋġu Co, a nonprofit group on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. Fuller, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said the organization works toward “wicozani,” or the good way of life, which encompasses the physical, emotional, cultural, and financial health of the community.

Siċaŋġu Co programs include bison restoration, youth development, a Lakota language immersion school, financial education, and food sovereignty initiatives.

“Some people out here that are struggling, they have dreams, too. They just need the resources, the training, even the moral support,” Fuller said. “I had one person in our health coaching class tell me they just really needed someone to believe in them, that they could do it.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Here’s a look back on who was on ‘Global News Morning Saskatoon’ for Tuesday, April 16.

15 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

Más condados prohíben el fluoruro en el agua potable. Cómo afecta a la prevención dental

Regina Barrett, una jubilada de 69 años que vive en Monroe, una pequeña ciudad de Carolina del Norte, al sureste de Charlotte, hace tiempo que no está contenta con el agua del grifo.

“Nuestra agua ha estado turbia y burbujeante, y parece lechosa”, dijo Barrett, que culpa al fluoruro, un mineral que comunidades de todo el país han agregado durante décadas al suministro de agua para ayudar a prevenir las caries y mejorar la salud dental.

“¡No quiero flúor en nada!”, dijo Barrett, haciéndose eco de un número creciente de personas que no sólo dudan de la eficacia del mineral sino que también creen que puede ser perjudicial a pesar de décadas de datos que destacan sus beneficios económicos y para la salud pública.

En febrero, la Junta de Comisionados del Condado de Union, cuya sede es Monroe, votó 3-2 para dejar de agregar fluoruro al agua potable en la Planta de Tratamiento de Agua del Río Yadkin, la única fuente de agua operada por el condado, que es de su propiedad. Pero la decisión se produjo después de fuertes discusiones entre residentes y funcionarios.

“Mis hijos tuvieron la bendición de crecer con fluoruro en el agua y… tienen muy pocos problemas dentales”, dijo el comisionado Richard Helms antes de votar. Un colega lo vio de otra manera: “Dejemos de poner en el agua algo que esté destinado a tratarnos, y demos a la gente la libertad de elegir”, dijo David Williams.

El agua de Barrett proviene de la ciudad de Monroe, no de las instalaciones de Yadkin. Así que, por ahora, seguirá bebiendo agua enriquecida con fluoruro. “Sospecho de por qué agregan eso a nuestra agua”, dijo a KFF Health News.

Es un escenario que se desarrolla a nivel nacional. Desde Oregon hasta Pennsylvania, en los últimos años cientos de comunidades han dejado de agregar fluoruro a sus suministros de agua o han votado para evitar agregarlo.

Los partidarios de estas prohibiciones argumentan que a las personas se les debería dar libertad de elección. Dicen que la amplia disponibilidad de productos dentales de venta libre que contienen el mineral hace que ya no sea necesario agregarlo al suministro público de agua.

Los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC) dicen que si bien los productos que se compran en tiendas reducen las caries, la mayor protección se produce cuando se usan en combinación con la fluoración del agua.

El resultado de un caso federal en curso en California podría obligar a la Agencia de Protección Ambiental (EPA) a crear una norma que regule o prohíba el uso de fluoruro en el agua potable en todo el país.

Mientras tanto, la tendencia está haciendo sonar las alarmas entre los investigadores de salud pública que temen que, al igual que con las vacunas, el fluoruro pueda haberse convertido en víctima de su propio éxito.

Los CDC sostienen que la fluoración del agua comunitaria no sólo es segura y eficaz, sino que también produce importantes ahorros en los costos de tratamientos dentales. Los funcionarios de salud pública dicen que eliminar el fluoruro podría ser particularmente perjudicial para las familias de bajos ingresos, para quienes el agua potable puede ser la única fuente de atención dental preventiva.

“Si tienes que salir y recibir atención por tu cuenta, es un juego completamente diferente”, dijo Myron Allukian Jr., dentista y ex presidente de la Asociación Americana de Salud Pública. Millones de personas han vivido con agua fluorada durante años, “y no hemos tenido problemas de salud importantes”, afirmó. “Es mucho más fácil prevenir una enfermedad que tratarla”.

Según el grupo anti-fluoruro Fluoride Action Network, desde 2010, más de 240 comunidades en todo el mundo han eliminado el fluoruro de su agua potable o han decidido no agregarlo.

Sólo hay que mirar al condado de Union para ver cuán intensas pueden ser las discusiones. Generalmente cuando los comisionados se reúnen en el primer piso del Centro de Gobierno en el centro de Monroe, la mayoría de los asientos están vacíos. Pero las sesiones sobre la prohibición del fluoruro en los suministros públicos de agua estuvieron colmadas de gente, y los residentes que se inscribieron para hablar estaban divididos.

Una persona que habló el 5 de febrero comparó la fluoración del agua con un cinturón de seguridad. No “previene el accidente automovilístico, pero limita el daño causado”, dijo. Otro argumentó que no hay pruebas de que el fluoruro sea seguro o eficaz. “Es un hito potencial significativo para revertir más de 60 años de envenenamiento del público”, dijo, utilizando una afirmación no probada que a menudo utilizan los opositores a la fluoración.

Los opositores al fluoruro afirman que el mineral es responsable de todo, desde el acné hasta la presión arterial alta, desde los problemas de tiroides hasta el cáncer de huesos.

Los Institutos Nacionales de Salud (NIH) reconocen que, cuando se ingiere en cantidades extremadamente grandes, el fluoruro de los productos dentales o suplementos dietéticos puede causar náuseas, vómitos, dolor abdominal, diarrea, dolor de huesos e incluso la muerte en casos extremadamente raros.

Los bebés y niños que reciben demasiado fluoruro pueden sufrir decoloración o pequeñas lesiones en los dientes. En los adultos, el consumo excesivo de fluoruro durante períodos prolongados puede provocar fluorosis esquelética, una afección muy rara que causa dolor y rigidez en las articulaciones, huesos débiles, pérdida de masa muscular y problemas nerviosos.

Sin embargo, la dosis recomendada en el agua potable siempre ha sido pequeña. En 2015, el Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos (HHS) redujo la concentración óptima de fluoruro de 1,2 miligramos por litro a 0,7 mg/L.

Juneau, en Alaska, votó a favor de eliminar el fluoruro de su agua potable en 2007. Un estudio publicado en la revista BMC Oral Health en 2018 comparó los registros dentales de niños y adolescentes que recibieron atención dental por caries cuatro años antes y cinco años después que la ciudad dejara de agregar fluoruro al agua. El estudio encontró que los procedimientos relacionados con las caries y los costos de tratamiento fueron significativamente más altos en el último grupo.

Portland, en Oregon, es la ciudad más grande del país que se ha negado sistemáticamente a agregar fluoruro a su agua potable. Los votantes han rechazado repetidamente las medidas para agregarlo, primero en 1956 y la última vez en 2013.

A pesar de la fuerte recomendación de los médicos y dentistas locales, los votantes de Wichita, Kansas, han rechazado agregar fluoruro al agua varias veces, la más reciente en 2012.

El Distrito Municipal de Servicios Públicos de Brushy Creek en el condado de Williamson, en Texas, estuvo agregando fluoruro a su sistema de agua desde 2007, pero puso fin a esta práctica en diciembre pasado.

En 2016, los comisionados del condado de Collier, en Florida, optaron por no eliminar el fluoruro del sistema de agua. Pero revocaron por unanimidad esa decisión luego de una Declaración de Derechos de Libertad de Salud de 2023 en respuesta a covid-19 que emitió el condado a través de una ordenanza, “para salvaguardar los derechos y libertades de atención médica de los residentes del condado de Collier”.

La Autoridad del Agua de State College Borough, en Pennsylvania, dejó de agregar fluoruro al agua de sus 75,000 clientes en marzo de 2023. Los funcionarios citaron razones que habitualmente usan los activistas anti-fluoruro: la posible contaminación ambiental, preocupaciones sobre la libertad médica y posibles efectos adversos para la salud.

Un estudio publicado en JAMA Pediatrics en 2019, realizado en seis ciudades canadienses, asoció la exposición al fluoruro durante el embarazo con puntuaciones de coeficiente intelectual más bajas en los niños. Pero el estudio se basó en informes propios y ha sido criticado por sus aparentes deficiencias metodológicas.

En 2016, varios grupos de defensa del consumidor, incluidos Fluoride Action Network, Food & Water Watch y Moms Against Fluoridation, solicitaron a la EPA que pusiera fin a la fluoración del agua en virtud de la Ley de Control de Sustancias Tóxicas, alegando que importantes investigaciones demostraban que el fluoruro era neurotóxico en las dosis usadas actualmente. El mismo grupo presentó una demanda federal contra la EPA al año siguiente, después que la agencia denegara la petición.

Durante un juicio de 10 días en San Francisco, que concluyó a mediados de febrero, las dos partes debatieron los riesgos y las áreas de incertidumbre. Si el juez federal de distrito Edward Chen determina que la fluoración del agua presenta un “riesgo irrazonable” para la salud humana, la EPA se verá obligada a crear una norma que regule o prohíba la fluoración del agua en Estados Unidos. Se espera una decisión pronto.

Por el momento, las decisiones sobre la fluoración de los sistemas de agua comunitarios todavía se toman principalmente a nivel local, lo que Barrett espera que cambie.

“De todas las cosas, lo que más quieren es que nuestros dientes estén sanos cuando faltan las necesidades básicas de vivienda y alimentación”, expresó.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

15 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

Winnipeg’s first responders need more mental health support, destigmatization: advocates

First responders deal with the same stresses as other workers, but the danger and trauma they experience can make things worse, said the United Firefighters Union president.

Social Services Minister Lionel Carmant announces measures to better support mental health patients in the southwest region of Montreal

15 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

Casi 1 de cada 4 adultos desafiliados de Medicaid siguen sin seguro, indica encuesta

Casi una cuarta parte de los adultos que fueron dados de baja de Medicaid el año pasado dicen que ahora no tienen seguro, según una encuesta que detalla cómo decenas de millones de estadounidenses lucharon por conservar la cobertura del gobierno para personas de bajos ingresos.

Las protecciones que tuvo el programa durante la pandemia, que impedían que se expulsaran beneficiarios, expiraron la primavera pasada.

La primera encuesta nacional sobre estas desafiliaciones de Medicaid halló que casi la mitad de las personas que perdieron la cobertura volvieron a inscribirse semanas o meses después, lo que sugiere que, en primer lugar, nunca debieron ser expulsadas.

Mientras que el 23% informó no tener seguro, un 28% adicional encontró otra cobertura: a través de un empleador, Medicare, el mercado de seguros de la Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA) o en programas para miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas, informó la encuesta de KFF.

“El 23% es una cifra sorprendente, especialmente si se piensa en la cantidad de personas que perdieron la cobertura de Medicaid”, dijo Chima Ndumele, profesora asociada de políticas de salud en la Escuela de Salud Pública de la Universidad de Yale.

Quedarse sin seguro, incluso por un período corto de tiempo, puede llevar a las personas a retrasar la búsqueda de atención médica, y exponerlas a riesgos financieros.

Siete de cada 10 adultos desafiliados dijeron que se quedaron sin seguro al menos temporalmente cuando perdieron su cobertura de Medicaid.

Adrienne Hamar, de 49 años, de Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, dijo que tuvo dificultades para inscribirse en un plan de ACA este invierno después que el estado le informara que ella y sus dos hijos ya no calificaban para Medicaid. Estaban inscritos desde 2020. Dijo que las líneas telefónicas estaban siempre ocupadas en el mercado estatal y que no podía completar el proceso en línea.

Hamar, que trabaja como asistente de salud a domicilio, y sus hijos, estuvieron sin seguro durante marzo. Pero desde el 1 de abril, están inscritos en un plan del mercado que, con la ayuda de subsidios gubernamentales, cuesta $50 al mes para la familia.

“Me sentí muy aliviada”, dijo. Hamar dijo que, por esta situación, su hija de 23 años demoró en hacerse un chequeo dental.

Las luchas de Hamar eran comunes, según la encuesta.

De los adultos inscritos en Medicaid antes de la cancelación, alrededor del 35% que intentó renovar su cobertura describió el proceso como difícil, y cerca del 48% dijo que era al menos algo estresante.

Alrededor del 56% de las personas dadas de baja dicen que omitieron o retrasaron atención médica o buscar una receta mientras intentaban renovar su cobertura de Medicaid.

“Es probable que el estatus actual del seguro de las personas esté cambiando, y esperaríamos que al menos algunas de las que dicen que actualmente no tienen seguro se vuelvan a inscribir en Medicaid (muchos dijeron que todavía lo están intentando) o se inscriban en otra cobertura en poco tiempo”, dijo Jennifer Tolbert, coautora del informe de KFF y directora del Programa Estatal de Datos y Reforma de Salud de la fundación.

La encuesta no incluyó a niños, y los investigadores de KFF dijeron que, por lo tanto, sus hallazgos no podían extrapolarse para determinar cómo la reducción de Medicaid ha afectado la tasa general de personas sin seguro en el país, que alcanzó un mínimo histórico del 7,7% a principios de 2023. Casi la mitad de los afiliados a Medicaid y al Programa de Seguro Médico Infantil (CHIP) son niños.

El proceso de desafiliación, durante el cual los estados están reevaluando la elegibilidad para Medicaid entre millones de estadounidenses que se inscribieron antes o durante la pandemia —y eliminando a aquellos que ya no califican o no completaron el proceso de renovación— no se completará hasta finales de este año.

La inscripción en Medicaid y CHIP creció a un récord de casi 94,5 millones en abril del año pasado, tres años después que el gobierno federal prohibiera a los estados eliminar a las personas de sus listas durante la emergencia de salud pública de covid-19.

A nivel nacional, los estados cancelaron la inscripción e Medicaid de alrededor de 20 millones de personas el año pasado, la mayoría por razones de procedimiento, como no presentar la documentación requerida. Se espera que ese número aumente, ya que los estados tienen algunos meses más para redeterminar la elegibilidad de los inscritos.

Entre los adultos que tenían Medicaid antes del inicio de las desafiliaciones, el 83% retuvo su cobertura o se volvió a inscribir, mientras que el 8% encontró otro seguro y el 8% no tenía seguro.

La proporción que quedó sin seguro fue mayor en los estados que no han ampliado Medicaid bajo ACA (17%) comparado con los estados que sí lo han hecho (6%). Cuarenta estados han ampliado Medicaid para cubrir a todas las personas con ingresos inferiores al 138% de la tasa federal de pobreza, o $31,200 para una familia de cuatro en 2024.

La encuesta de KFF encontró que casi uno de cada 3 adultos a los que se les canceló el seguro descubrió que ya no tenían Medicaid recién cuando buscaron atención médica, como ir a un médico o a una farmacia.

Indira Navas, de Miami, descubrió que a su hijo Andrés, de 6 años, se le había dado de baja del programa de Medicaid de Florida cuando lo llevó a una cita con el médico en marzo. Había programado esa cita con meses de anticipación y está frustrada porque el niño sigue sin seguro y se interrumpió su terapia para la ansiedad y la hiperactividad.

Navas dijo que el estado no pudo explicar por qué su hija Camila, de 12, seguía cubierta por Medicaid a pesar de que los dos niños viven en el mismo hogar que sus padres.

“No tiene sentido que cubran a uno de mis hijos y al otro no”, dijo.

Kate McEvoy, directora ejecutiva de la Asociación Nacional de Directores de Medicaid, dijo que el gran volumen, de millones de personas, a las que se está analizando para determinar su elegibilidad ha abrumado a algunos centros de llamadas estatales que intentan apoyar a los afiliados.

Dijo que los estados han probado muchas formas de comunicarse con los inscritos, incluso a través de campañas de divulgación pública, mensajes de texto, correo electrónico y aplicaciones. “Hasta el momento en que su cobertura está en juego, es difícil penetrar en las vidas ocupadas de las personas”, dijo.

La encuesta de KFF, de 1,227 adultos que tenían cobertura de Medicaid a principios de 2023 antes del inicio del proceso de desafiliación, el 1 de abril de 2023, se realizó entre el 15 de febrero y el 11 de marzo de 2024. El margen de error de muestreo fue de más o menos 4 puntos porcentuales.

El corresponsal de KFF Health News, Daniel Chang, colaboró con este artículo.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

15 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

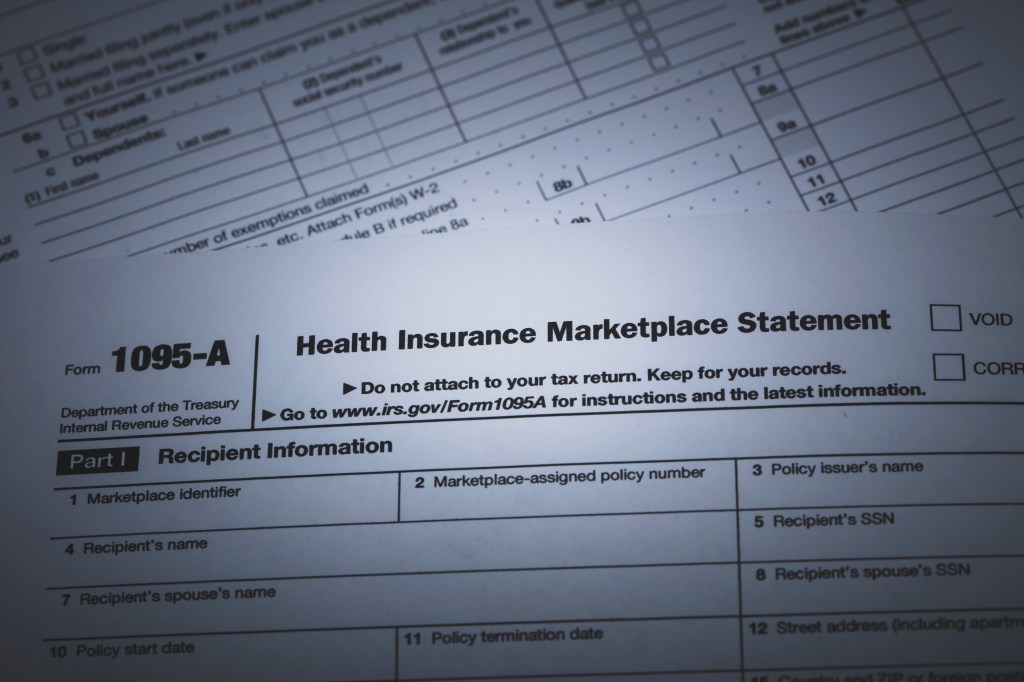

When Rogue Brokers Switch People’s ACA Policies, Tax Surprises Can Follow

Tax season is never fun. But some tax filers this year face an added complication: Their returns are being rejected because they failed to provide information about Affordable Care Act coverage they didn’t even know they had.

While the concern about unscrupulous brokers enrolling unsuspecting people in ACA coverage has simmered for years, complaints have risen in recent months as consumers discover their health insurance coverage isn’t what they thought it was.

Now such unauthorized enrollments are also causing tax headaches. Returns are getting rejected by the IRS and some people will have to pay more in taxes.

“It’s definitely gotten worse over the past year. We’ve helped three to four dozen people this year already,” said Erin Kinard, director of systems and intake for the Health and Economic Opportunity Program at Pisgah Legal Services in North Carolina, which helps low-income families enroll in ACA plans and get tax help.

Neither the IRS nor the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which oversees the federal Obamacare marketplace, responded to questions about the problem.

The IRS did, however, issue an FAQ in February instructing consumers on what to do if their electronically filed returns are rejected because of ACA issues.

Unauthorized sign-ups can happen in several ways, Kinard and others said. Some rogue agents troll online enrollment portals that are accessible only to brokers but are integrated with the healthcare.gov website. When those agents open a new policy or switch an already enrolled policyholder to a different plan, they garner the associated monthly commissions. Other consumers unwittingly sign up when they respond to advertisements touting gift cards or government subsidies then are transferred to agents who enroll them in health coverage. It’s happening even after new rules were put in place requiring agents to get written or recorded consent from clients before making changes.

CMS has not released details on how many consumers have been affected or how many agents have been sanctioned for participating in such schemes.

There’s also no public tally of how many taxpayers are facing problems as a result. And the tax consequences can come as a surprise.

“Many people are finding out when they go to e-file their taxes and it bounces back and the IRS says it can’t accept your return,” said Christine Speidel, an associate professor and the director of the Federal Tax Clinic at Villanova University’s Charles Widger School of Law.

Returns are rejected if the IRS has information indicating the taxpayer has ACA coverage but the returns don’t include forms that help determine whether premium tax credits paid on the policyholder’s behalf to insurers were correct. If their income was misstated by the rogue broker who enrolled them, for example, they might not have qualified for the full amount paid. Or, if they had affordable employer coverage, they would not have been eligible for ACA subsidies at all.

Ashley Zukoski, an ultrasound technologist in Charlotte, North Carolina, had employer coverage but now faces a tax bill for an ACA plan she said she never signed up for. She reached out to KFF Health News after it reported on such unauthorized plan enrollments.

Unbeknownst to her, she said, a broker in Florida enrolled her family in an ACA plan in late February 2023, even though Zukoski had coverage starting that January through her job. The broker listed an income that qualified the household for a full subsidy, so Zukoski never received a premium bill.

Her first inkling that something was amiss came early in 2024 when she received a special form, called a 1095-A, which showed she had an ACA plan. After reporting the problem to the federal marketplace, she sought to get the 1095-A voided so she would not be liable for the plan’s premium subsidies paid by the government to the insurer.

But, because Zukoski’s pharmacy had billed the ACA plan instead of her job-based coverage, her request was denied. She plans to appeal.

In the meantime, the family has filed an extension on their taxes.

“Instead of getting a $4,100 refund, we now owe almost $700 in taxes based on the 1095-A and premium tax credit applied,” Zukoski said.

With the April 15 federal tax filing deadline upon us, there are some important steps for affected consumers to take, tax and insurance experts said.

First, because it could take weeks to get corrected forms, experts recommend filing for an extension to buy more time. When consumers file for that extension, they should also pay any taxes owed to avoid penalties and interest.

In general, consumers who at any point in the year think they are victims of an unauthorized enrollment or plan switch should report it immediately to the relevant federal or state ACA marketplace and request a corrected Form 1095-A. But move fast. Appeals to cancel coverage retroactively must be made within 60 days of discovering the fraudulent enrollment, Speidel said.

Consumers can ask for help filing a complaint with federal or state regulators by contacting their own insurance agents or seeking help from assisters or “navigator” programs, which are government-funded nonprofit groups that help people enroll or deal with insurance problems.

Navigators and assisters are fielding many such cases this year and can submit what are called “complex case forms,” which help federal officials investigate such complaints, said Lynn Cowles, program manager for Prosper Health Coverage, a navigator program in Texas.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

12 Apr, 2024 | Admin | No Comments

Nearly 1 in 4 Adults Dumped From Medicaid Are Now Uninsured, Survey Finds

Nearly a quarter of adults disenrolled from Medicaid in the past year say they are now uninsured, according to a survey released Friday that details how tens of millions of Americans struggled to retain coverage in the government insurance program for low-income people after pandemic-era protections began expiring last spring.

The first national survey of adults whose Medicaid eligibility was reviewed during the unwinding found nearly half of people who lost their government coverage signed back up weeks or months later — suggesting they should never have been dropped in the first place.

While 23% reported being uninsured, an additional 28% found other coverage — through an employer, Medicare, the Affordable Care Act’s insurance marketplace, or health care for members of the military, the survey by KFF found.

“Twenty-three percent is a striking number especially when you think about the number of people who lost Medicaid coverage,” said Chima Ndumele, an associate professor of health policy at the Yale University School of Public Health.

Going without insurance even for a short period of time can lead people to delay seeking care and leave them at financial risk when they do.

Seven in 10 adults who were disenrolled during the unwinding process say they became uninsured at least temporarily when they lost their Medicaid coverage.

Adrienne Hamar, 49, of Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, said she struggled to enroll in an Affordable Care Act marketplace plan this winter after the state informed her that she and her two children no longer qualified for Medicaid. They had been enrolled since 2020. She said phone lines were busy at the state’s marketplace and she couldn’t complete the process online.

Hamar, who works as a home health aide, and her children were uninsured in March. But since April 1, they’ve been enrolled in a marketplace plan that, with the help of government subsidies, costs $50 a month for the family.

“I was very relieved,” she said. Unsure of their insurance status, Hamar said, her 23-year-old daughter delayed getting a dental checkup.

Hamar’s struggles were common, the survey found.

Of adults enrolled in Medicaid before the unwinding, about 35% who tried to renew their coverage described the process as difficult, and about 48% said it was at least somewhat stressful.

About 56% of those disenrolled say they skipped or delayed care or prescriptions while attempting to renew their Medicaid coverage.

“People’s current insurance status is likely to be very much in flux, and we would expect at least some of the people who say they are currently uninsured to reenroll in Medicaid — many say they are still trying — or enroll in other coverage within a short period of time,” said Jennifer Tolbert, a co-author of the KFF report and the director of KFF’s State Health Reform and Data Program.

The survey didn’t include children, and the KFF researchers said their findings therefore couldn’t be extrapolated to determine how the Medicaid unwinding has affected the overall U.S. uninsured rate, which hit a record low of 7.7% in early 2023. Nearly half of enrollees in Medicaid and the related Children’s Health Insurance Program are children.

The unwinding, in which states are reassessing eligibility for Medicaid among millions of Americans who enrolled before or during the pandemic and dropping those who no longer qualify or did not complete the renewal process, won’t be completed until later this year. Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP grew to a record of nearly 94.5 million in April of last year, three years after the federal government prohibited states from cutting people from their rolls during the covid-19 public health emergency.

Nationally, states have disenrolled about 20 million people from Medicaid in the past year, most of them for procedural reasons such as failure to submit required paperwork. That number is expected to grow, as states have a few more months to redetermine enrollees’ eligibility.

Among adults who had Medicaid prior to the start of the unwinding, 83% retained their coverage or reenrolled, while 8% found other insurance and 8% were uninsured. The share left uninsured was larger in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA (17%) than in states that have (6%). Forty states have expanded Medicaid to cover everyone with an income under 138% of the federal poverty rate, or $31,200 for a family of four this year.

The KFF survey found that nearly 1 in 3 disenrolled adults discovered only when they sought health care — such as going to a doctor or a pharmacy — that they had been dropped from Medicaid.

Indira Navas of Miami found out that her 6-year-old son, Andres, had been disenrolled from Florida’s Medicaid program when she took him to a doctor appointment in March. She had scheduled Andres’ appointment months in advance and is frustrated that he remains uninsured and his therapy for anxiety and hyperactivity has been disrupted.

Navas said the state could not explain why her 12-year-old daughter, Camila, remained covered by Medicaid even though the children live in the same household with their parents.

“It doesn’t make sense that they would cover one of my children and not the other,” she said.

Kate McEvoy, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, said the sheer volume of millions of people being redetermined for eligibility has overwhelmed some state call centers trying to support enrollees.

She said states have tried many ways to communicate with enrollees, including through public outreach campaigns, text, email, and apps. “Until the moment your coverage is at stake, it’s hard to penetrate people’s busy lives,” she said.

The KFF survey, of 1,227 adults who had Medicaid coverage in early 2023 prior to the start of the unwinding on April 1, 2023, was conducted between Feb. 15, 2024, and March 11, 2024. The margin of sampling error was plus or minus 4 percentage points.

KFF Health News correspondent Daniel Chang contributed to this article.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).